Prologue: The Forests That Remember

In a world rushing toward skyscrapers and satellite signals, there remain places that remember centuries, millennia, even epochs. These are forests that carry in their leaves, roots, soil, and air the memory of ancient climates, vanished beasts, evolving species, and human footsteps, faint and few.

I have walked many such places. This blog is about one of those rich places, the great rainforests of the southern Caspian, the oak-carpeted hills of the Zagros, the misty ridges near Masal, the silent slopes once patrolled by tigers. Over the years, nine years ago, two years ago, and other years, during the recent fires, I returned to the memories of these forests, remembering that I had drawn breath in their damp air, sifted their leaf litter for bones and feathers, catalogued their insects under a lamp, carried their stories with me into conference rooms and conservation halls.

I hold in my memory, and on my hard drive, the fragments of what was: evenings filled with moths, snake vertebrae under deadwood, a skull fragment half-buried in moss, wild boar eyes glinting in the night, five delicate feathers of a Eurasian Jay, the echo of my grandfather’s memories. I carry these like relics as witnesses to a living world that may be lost.

This is the story of those forests. Their grandeur, their fragility, their bloodline with time, and the call to save them before the pages of their history burn away.

HYRCANIAN FORESTS: A 25–50 Million-Year-Old World

Stretching along the southern coast of the Caspian Sea, from the quiet marshes at sea level to the steep slopes of the Alborz mountains, the forests known as Hyrcanian form one of the oldest, most biologically significant temperate forest ecoregions on Earth. According to the documentation of their designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, these forests trace their living heritage back 25 to 50 million years, surviving glacial cycles, sea-level swings, ice ages, and shifting continents. (Apa.az)

Today, the core protected parts of these forests cover nearly 2 million hectares, though historically the forest stretched far more widely, which was an echo of the green corridors that once connected much of temperate Eurasia. (Tehran Times)

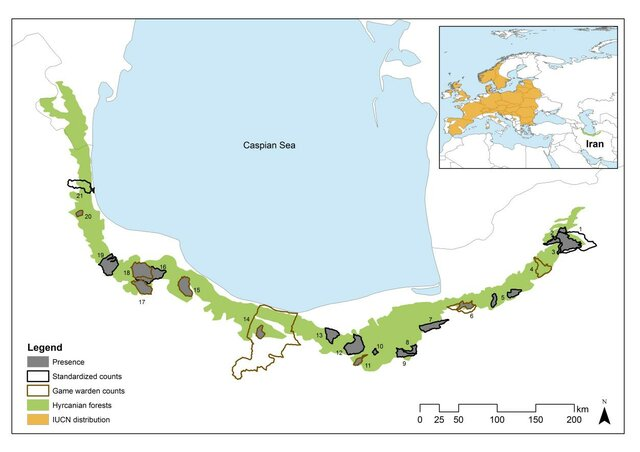

Map showing the locations of the 21 survey sites across the Hyrcanian forests in northern Iran (numbered 1–21) with the known extent of forest cover (derived from 1-km-resolution global land-cover data, adapted to a Hyrcanian forests map) overlaid; red-deer (Cervus elaphus maral) presence is indicated in grey shading across sites. The inset shows the broader IUCN-assessed distribution of the red deer species across its global range (orange).(Researchgate)

Biodiversity: A global treasure in a temperate latitude

Many have little idea of the presence of forests in Iran, thinking of it as a desert country similar to other middle eastern countries. The biodiversity here is staggering especially for what many assume is “just another temperate forest.” By recent botanical and ecological surveys, more than 3,200 vascular plant species have been documented in the Hyrcanian region. That number alone constitutes roughly 44% of all vascular plant species recorded in Iran, even though the Hyrcanian occupies a small fraction of the country’s land area. (Unesco)

Among those are approximately 280 endemic or sub-endemic taxa, meaning they occur nowhere else which area living relics of past climates and ancient evolutionary paths. (Apa.az)

Birdlife is rich: around 180 bird species typical of broad-leaf temperate forests have been recorded here, ranging from warblers to raptors. Mammals number at least 58 recorded species, including large predators such as the Persian leopard, wolves, and brown bears — proof of a still-functioning, complex ecosystem from ground floor to canopy crown. (Apa.az)(Unesco)

Even the trees are ancient: many of the largest oaks, hornbeams, beeches, and the legendary Persian Ironwood stand for 300–400 years, some perhaps nearing 500 years old. (Apa.az)

So thus far we come to realise that these are not a fragmented woodland but a living cathedral, perhaps a forest of global heritage.

https://www.instagram.com/p/DPlXZpPEuvW/

My First Return: Nine Years Ago

I still remember the first time I walked deep into the Hyrcanian forest, however more vividly nine years ago. I recorded in my book that it was “the richest experience” of my life. (TYEC)

There were no roads , only narrow animal paths and the heavy scent of damp earth and decaying leaf litter. Underfoot, leaves, chestnut, beech, hornbeam, pressed down, releasing the rich smell of humus, wood decay, and ancient soil. Everything smelled of endings and beginnings, life and death intertwined.

I crouched beneath a fallen trunk; under its wet, rotten bark, I discovered a snake vertebra curved, narrow, hollowed, this was a silent bone abandoned by some predator or natural death. As evening fell I set up a simple white sheet between two trees and switched on a mercury-vapor lamp. The forest that had seemed hushed during the day exploded into motion.

First: mosquitoes, you would hear a soft buzz around your ears, flashing eyes, drawn like moths to flame, literally. Then, as though the forest had been waiting for an invitation, the night insects emerged in a grand pageant:

- Moths with leaf-mimicking camouflage, wings folded like dead wood

- Stick-insects that froze when disturbed, indistinguishable from twigs

- Beetles, some with iridescent shells, some with dull carapaces, all alive with movement

- Predatory spiders casting thin silken threads down in search of prey

- Wasps; some winged, some ant-like or parasitic

Being just 12, I spent hours observing them, one by one. At that moment, I understood what true biodiversity means: layers upon layers of life, often invisible during the day, but essential to the functioning of entire ecosystems.

Bones and Echoes: The Snake Spine and the Skull Fragment

In subsequent visits I returned to that same place. Under the wet leaf litter, under rotting logs, I found more evidence of life and death interwoven.

The snake vertebra which was delicate, hollowed, ancient under the forest’s damp chill. I wondered: which snake had that backbone? A forest viper? A slender colubrid? No record; no markings but the universal geometry of vertebral rings.

Nearby, I discovered a small skull. Perhaps I thought it would belong to a rodent or shrew, but after careful analysis many years later I am sure it belongs to the mongoose family.. The lower jaw was long gone, only the cranium was left . The next day I also found an Indian Porcupine quill. These all were evidence that even small creatures thrive here, that predators hunt, that life feeds on life, and that the forest’s nutrient-cycle web runs from fungus to rodent to predator to leaf litter to mycelium again.

Ancestral Shadows: The Caspian Tiger

On a different axis of memory lies a story passed down through my family.

My grandfather once travelled through Mazandaran. In 1966, he saw a striped cat cross the road, perhaps it was a tiger, maybe not, but it was a powerful, sleek feline with a gait like rippling water, disappearing into the forest in one silent bound, at night. He said nothing then; he did not know if it was rare. But to me, decades later, his memory became a hinge. A hinge between what was and what is no more.

The great Caspian tiger (Panthera tigris virgata) was once the master of these forests, it was a top predator, a symbol not just of wilderness but of ecological balance. By the mid-20th century, however, its fate was sealed: hunting, habitat destruction, human encroachment. Small numbers remained into the 1950s and 1960s. My grandfather’s sighting may have been among the last.

Today, the forests remember. The trees stand but the stripes are gone. The silence is heavier. The prey animals multiply but the predator that once held the line is gone. The extinction of the Caspian tiger is a wound in the forest’s story; a fracture in an ecosystem that had existed for millions of years. This forest does not only hold living memory, it holds losses.

MASAL AND THE WESTERN EDGE OF THE HYRCANIAN

Two years ago I traveled to Masal, a place where cloud and forest merge, where ridges are veiled in mist and the trees lean heavy with dew. Locals warned me: wild boar frequent these slopes at night. They roam in soundless herds, disturb soil and roots, move like ghosts.

Behind the little house we stayed in I ventured in the backyard, the borders of the house fences, that night I walked alone under the oak-beech canopy, the path soft with moss and damp leaves. I carried a torch, stepping carefully, listening. Then, a flash of reflected light. Eyes. Two pairs. Then another. At a distance, six glowing eyes, silent but aware. Wild boars, watching me. Then, as silently as they appeared, they were gone, melting into the darkness between trunks. I froze. In that instant I felt the forest watching me back not with hostility, but with calm, cautious awareness.

Wild boar (Sus scrofa) are not villains. They are ecosystem engineers. Their rooting and digging churn the soil; their feeding shapes young saplings and undergrowth; their presence influences seed-dispersal, fungal networks, insect communities, small mammal distribution. To see their eyes in the night is to see the heart of a functioning forest.

On that same trip, I again set up my night sheet and lamp. The show was familiar with mosquitoes, moths, beetles, spiders, but this time cicadas and other insects joined this symphony, but it also felt different. Some species I had never seen before; others shifted in abundance and pattern. Night after night, I photographed, documented, uploaded to iNaturalist, I later reflected on them during the fires, those observations reaching research grade and being an archive.. I became an informal census taker for the forest’s nocturnal world. To me, the Masal forest was alive in its breathing, in its roots, in its glowing eyes.

The Five Feathers: A Brooch, a Conversation, a Call

On another walk during the day, under tall oaks, I found five feathers, which were small and delicate. They belonged to a common, clever woodland bird: the Eurasian Jay (Garrulus glandarius). Alula feathers from the wing, covert feathers from the shoulder, each softly iridescent, patterned in blues and blacks, each dropped quietly, naturally, on the forest floor. Over time I had a beautiful collection of a few feathers, I had collected from these forests over the years.

I collected them carefully ,I cleaned them, dried them, and stored them. Then, some months later, I fashioned a single brooch-pin from three of Eurasian Jay feathers, two from the Helmeted Guineafow I collected on the same day as the Eurasian Jay feathered near a road side, a feather from Red Junglefowl, Eurasian Magpie, Chukar and Rose-ringed Parakeet .

I wore that brooch for a reason: to carry the forest, Nature and their fragility with me, to bring its heartbeat into rooms of policy and decision.

As you read further you will come across my campaign for these forests and their diversity, but I also regret the absence of Dr Jane Goodall to join me as Sir David Attenborough did. But I recall just months earlier, I shared the stories of this forest coincidentally, that was when I met a woman I have long admired: Dr. Jane Goodall in February 2025. Earlier when we met, I gave her a feather painting, later when she saw me to have our deep conversation, She looked and pointed out the brooch. I remember she traced its feather edge with gentle fingers. Asking me what's the story of this brooch. I responded by telling that this brooch carries a piece of the forests I have walked and loved. I collected a few feathers I found from birds in the Hyrcanian forests; Eurasian Jay, Helmeted Guineafowl, Red Junglefowl, Eurasian Magpie, Chukar, and Rose‑ringed Parakeet and carefully preserved them. I then attached them to a small Caucasian Oak acorn I had cut, creating a single pin. I wear it to carry the heartbeat of the forest, a fragile reminder of Nature’s beauty, resilience, and the urgent need to protect it. I also went into a little bit of details about the forests, things you have read so far.. Then, she said, in a quiet but firm voice:

“Ah… this is so beautiful. It carries the voices of the birds, the whispers of the Hyrcanian forests, and the lives of all who depend on them. Never stop telling their story, that is how we inspire others to care for this precious world.”

Her words became a vow for me.

A vow to speak.

A vow to remember.

Peoples of the Zagros: Lives Intertwined with Oaks and Mountains

Far from the humid slopes of the Caspian, stretching across western Iran, the Zagros Mountains rise; a vast, rugged spine of rock, oak woodlands, shepherd’s trails, and human history older than cities. Here, forest and culture have grown entwined for millennia.

Communities such as the Bakhtiari, Lur, Kurdish and others have long lived in seasonal migration, goat and sheep husbandry, selective oak harvesting, and customary forest use. Their lives depend on oak mast for livestock, wood for fuel and construction, small-scale agriculture, and the subtle rhythm of winter and summer in the mountains. These forests are not remote reserves. They are living cultural landscapes shaped by human footsteps as much as by acorns, wolves, and rain.

But pressure grows. Overgrazing, drought, fuel needs, land conversion, tree-cutting for wood and charcoal, people’s lack of understanding of biodiversity and nature, and now, increasing wildfire risk, all threaten the delicate balance that preserved these forests for generations. (Tehran Times)

Unless their custodians, and the global community, act, the Zagros oak woods may vanish as silently as the stripes of a tiger.

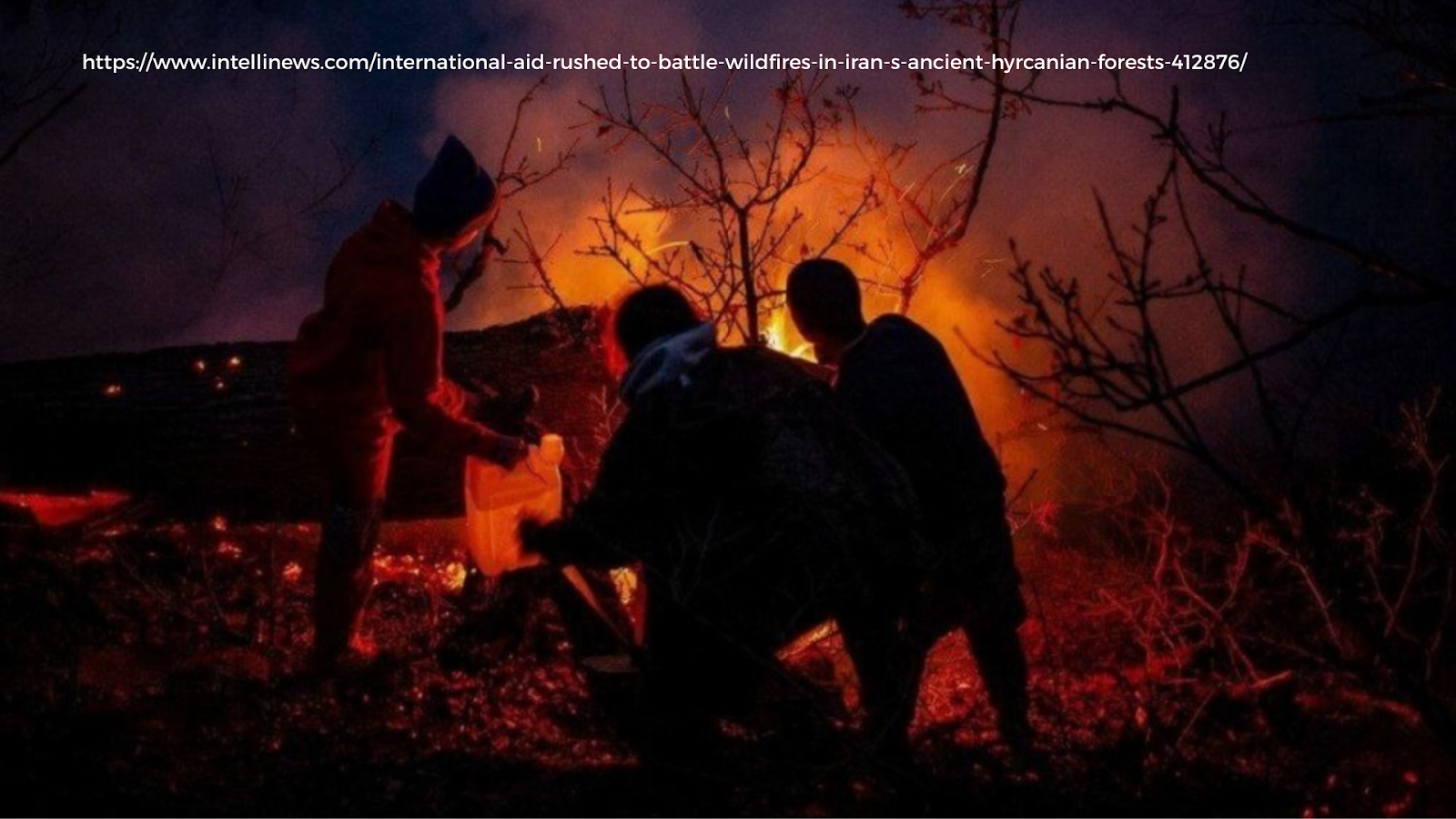

The 2025 Wildfires: When Memory Turned to Smoke

In late 2025, fire came to both memory and living forest. The ancient Hyrcanian woodlands, the 25–50-million-year-old rainforest that once covered swathes of Eurasia - burned.

According to official reports, Iran recorded 2,310 forest and rangeland fires in 2025, burning 18,009 hectares nationwide. (IranWire) The northern forests ; Hyrcanian, Zagros, Arasbaran were closed to tourists, local traffic and non-essential entry under a “red alert.” (Arab News)

In the Hyrcanian, the fire started near the village of Elit in Mazandaran. Initially contained, strong winds, dry vegetation, and extreme drought fanned the flames again. By mid-November, after more than a week, fires reignited; firefighting crews; hundreds of volunteers, forest wardens, mountain rescuers, and helicopter and aircraft support joined the effort. (ایران اینترنشنال). The forest was burning for more than 3 weeks.

Myself, activists, Authorities and others even appealed internationally. Planes from neighboring countries were dispatched to help contain the fire on steep, treacherous slopes near Marzanabad in Chalus. (Apa.az)

By 25 November 2025, officials declared the main blaze contained though smouldering hotspots remained under monitoring, and assessment of ecological damage had not yet begun. (Tehran Times)

Why these fires are more than forest fires

In many ecosystems whether the Mediterranean, boreal, or savannah, fire is part of the cycle. Species evolve in fire regimes. Seeds sprout after the flame. Regrowth begins quickly.

But the Hyrcanian forests are not fire-adapted in that way. They evolved in stability in humid rain, deep leaf litter, slow decomposition, slow growth, slow turnover; large, old broad-leaf canopies; rich fungal networks; intricate food webs. A single high-intensity fire can destroy leaf-litter, sterilize soil, kill delicate fungi, wipe out invertebrate communities, burn seedbanks, scorch saplings, kill ground-dwelling vertebrates leaving behind charred trunks, erosion-prone slopes, and a silence where there once was life.

Petitions, Letters, and a Call to the World

When the fires struck, I could not remain silent. I gathered my photos: the moth-sheet images, the snake vertebra, the skull fragment, the jay feathers, the night-vision boar-eyes, memories of those forest walks and I launched a petition. I addressed letters to WWF, UNEP, and the UNESCO World Heritage Centre, imploring them to recognize the damage, demand assistance, and mobilize resources. This was in the form of a public petition on Change.org titled “Help save the Hyrcanian forests from devastating fires.” Its goal was to draw international attention, rally global signatures, and to act. (Change.org) With your help and many others we gathered 272 petition signatures as of 5th December.

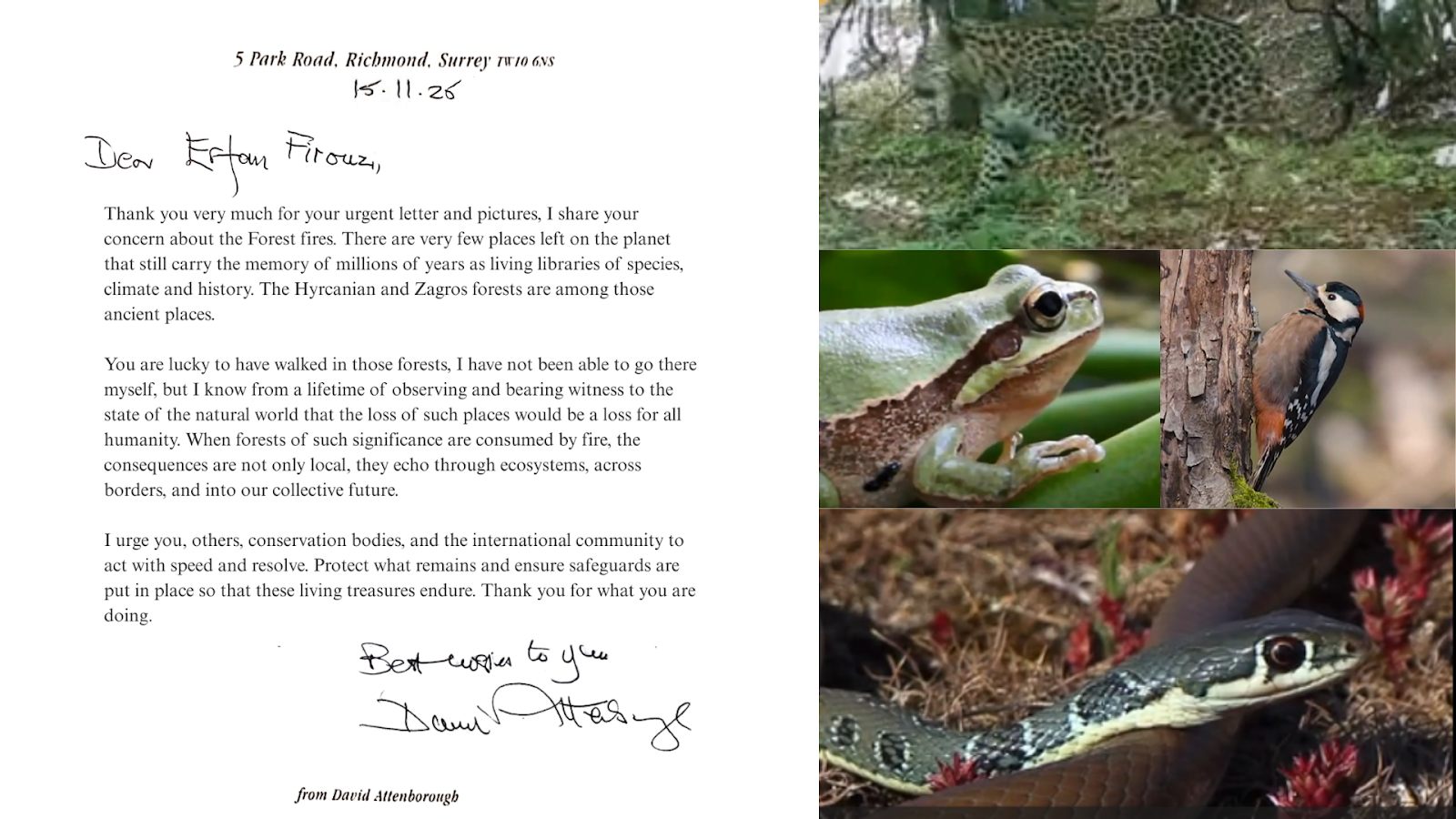

And I wrote to Sir David Attenborough attaching a few photos you have seen this far, and this was his reply:

“There are very few places left on the planet that still carry the memory of millions of years as living libraries of species, climate and history. The Hyrcanian and Zagros forests are among those ancient places. … When forests of such significance are consumed by fire, the consequences are not only local — they echo through ecosystems, across borders, and into our collective future.”

And I imagined his voice echoing: urgent, compassionate, resolute. His words became a plea and this story got 145k views, and countless people joined this journey.

Ecological consequences, what the fires can steal

- Loss of biodiversity layers: rare endemic plants, specialized fungi, ground insects, amphibians, small mammals; all vulnerable to high-intensity fire. Many are slow-growing, specialized species; their recovery, if at all, may take decades, maybe centuries or may never happen.

- Soil and hydrology collapse: Without canopy, without root networks, slopes erode. Heavy rains wash away topsoil. Watersheds change. Springs that for generations fed valleys may dry up; streams may become seasonal or vanish altogether.

- Loss of ecological memory: Seeds lost, seedbanks destroyed genetic lineages erased, microhabitats lost. In a forest that evolved in stability over millions of years, this is a rupture.

- Wildlife decline: Ground-dwelling species insects, amphibians, small mammals likely suffered massive mortality. Predators lose prey. Specialists vanish. Ecosystem balance is skewed.

- Cascading cultural and livelihood loss: Local communities that depend on mushrooms, herbs, acorns, forest grazing, medicinal plants lose resources; traditional knowledge, passed down generations, is at risk.

So this far we have realised that the forest does not only lose trees, it loses time.

These forests are not just wild places. They are homes, livelihoods, ancestral lands. Indigenous communities, shepherds, villagers, pastoralists their lives interlace with oak acorns, goat pastures, forest mushrooms, medicinal herbs, wood for winter fires.

When the forest hurts, people hurt too. When the forest dies their heritage wanes. Their future becomes uncertain. And globally , we lose a unique natural archive: a living record of evolution, resilience, adaptation, diversity. This is not only a national tragedy. It is a human tragedy. Our allies to climate change are dying throughout the world.

What is happening in the Hyrcanian is not just a tragedy of local ecology. It is a warning. As global climate warms, as drought intensifies, as human encroachment continues and we lose our connection with Nature, temperate forests once thought stable may become tinderboxes. Ancient forests may vanish, not in centuries, but in weeks. If the world does not pay attention not for the trees, but for the people, the species, the carbon, the water, the memory then the forest’s loss will echo far beyond Iran’s borders.

HOPE & RENEWAL: Can Forest Memory Resurge?

Amid the smoke, loss, and charred silence, there remains a fragile but real thread of hope. Not all is lost — not yet. There are glimmers: efforts underway, communities mobilizing, global actors paying attention, ecological science offering paths to recovery.

In June 2025, just months before the devastating fires, a high-level conference in Tehran brought together Iranian ministries, UN agencies, civil society, and foreign diplomats under the banner of “Sustainable Management of the Zagros Forests.” The conference reaffirmed that the Zagros woodlands, constituting 40% of Iran’s entire forest cover, are a heritage for Iran and for humanity. Officials declared that sustainable forest management must become a priority — for climate resilience, water security, and ecological stability. (iran.un.org)

Programs were proposed for community forestry, seedling propagation, watershed and slope stabilization, and participatory forest governance. As of 2023, plans called for planting seedlings or sowing seeds over more than 50,000 hectares of degraded oak woodlands in the Zagros. (Tehran Times)

But these efforts are not abstract or bureaucratic gestures, they are animated by people: the volunteers who went into the forests to monitor conditions, update us on wildlife sightings, share their stories of the forests’ hidden wonders, and even help fight the fires directly. From local villagers wading through smoke-filled slopes, to rangers and biologists assessing post-fire damage, people have put their hands, hearts, and time into these forests. Their stories, shared with me, are testimony that hope is not passive, it is lived, breathed, and enacted.

In this human network of care, mentorship and inspiration have been crucial. Lessons from figures like Dr. Jane Goodall remind me that hope is not naïve optimism: it is the persistent act of showing people why the forests, the animals, the stories, and even a single feather or fallen leaf matter. She taught me that moving people, conveying wonder, telling stories, and celebrating the life that remains can ripple outward, mobilizing others to act. That lesson resonates deeply in Iran’s forests today: each report, each shared photograph, each personal action contributes to the revival of hope. Every volunteer who stood at the edge of smoke, every scientist who mapped burned zones, every local villager who helped extinguish flames, every child learning the names of oaks, ferns, and beetles, all are threads in the same tapestry.

Hope, in these forests, is collaborative and contagious. It is in the seedlings planted after the fire, in the saplings nurtured by communities, in global attention toward policy and conservation, and in the personal stories that travel from the forest floor to international halls of decision-making.

These actions whether collective, individual, local, or global demonstrate that recovery is possible, that forests can breathe again, and that the legacy of these ancient woodlands is not yet extinguished. Amid charred trunks and blackened soil, I have seen people, mentorship, and community create pathways to renewal, showing that hope is not a quiet sentiment, it is a force as alive and enduring as the forests themselves.

Just a few days ago, nature reclaimed its dominion. Rain returned, soaking the scorched soil, stirring roots, and finally extinguishing the fires that had ravaged the Hyrcanian and Zagros forests. Yet this reprieve is a stark lesson: a cigarette, a careless barbecue, or any spark can ignite devastation in moments. We must approach these forests not as conquerors, but as witnesses feeling the damp moss beneath our feet, smelling wet leaves, noticing the shimmer of a bird’s wing.

The rains remind us of hope, renewal, and the forest’s enduring heartbeat. But survival depends on respect, care, and reverence. These forests are living libraries; we are their stewards, not masters.

What I Still Believe And What You Can Do

Globally recognized bodies such as the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) have weighed in, advising that sustainable forest management (SFM) combined with community engagement, reforestation, adaptive governance, and climate-finance tools can rebuild degraded woodlands and reverse loss. (Tehran Times)

In Zagros, the plan is to include local communities directly; shepherds, pastoralists, indigenous people. Their traditional knowledge, their seasonal wisdom, their rooted connection to the land becomes part of the forest’s future. A community-forestry approach anchors forest as both ecological and human heritage as living landscapes, not reserves behind fences. (Tehran Times)

I still believe the forest can heal if we give them the chance and support they need.. Not all. But parts. Pockets. Corridors. Refugia. Remnant groves where old trees survive, where seed banks survive underground, where insects, fungi regenerate, mycelial webs rebuild.

Because I have the photos. The moth sheets. The snake vertebra. The jay feather. The skull fragment. The memory of those nights.The way we connected with Dr Jane Goodall, Sir David Attenborough and many others And I am not alone: many Iranians, many global citizens, feel the same grief and the same duty.

What can you do? wherever you are in the world:

- Support restoration efforts: sign petitions, back community forestry, fund seedling programs, encourage reforestation.

- Raise awareness: share stories, photographs, maps; talk about the forests as global heritage, not remote wilderness.

- Push for policy change: ask for stronger fire-prevention infrastructure; demand protected area enforcement; promote sustainable forestry and indigenous stewardship.

- Document and archive: if you have photographs, observations, traditional knowledge. treat them as precious. Forest memory includes human memory.

- Bear hope, carry hope: wear the feather brooch, tell the stories, speak in halls of power, speak softly but firmly to those who govern forests, money, and resources.

Restoration will not be easy. It will take years, decades perhaps. But if we remember and work together, if we act we can offer these forests a chance to whisper again and quickly recover.

Epilogue: The Memory of Leaves

I have returned many times. I will return again, if I can. I still hope. For mushroom rings under fallen logs. For moths fluttering on white sheets. For snake slithering around under decaying bark. For owl pellets, falling feathers, boar tracks, wolf howls in valleys I know by name. For jay feathers worn as brooches at climate conferences, as symbols; as small, fragile calls to remember.

I write this not only as a memory. Not only as a lament. But as a plea. To scientists, to governments, to people who read this in cities far from the Caspian:

Listen.

A forest is not just wood and leaf and soil. It is time, memory, lineage, life. And once it burns, that chapter may be lost forever. If we still have a chance, let us be its guardians. Let us not fail it.

Comments